The full impact of the Supreme Court’s June 2023 ruling that colleges can’t consider race in admissions may not be known for years. But a CBS News analysis of enrollment records shows the first class of freshmen since the high court’s order is a little less diverse than the class before it.

College admissions experts say there are signs campuses will trend toward less diversity at the same time some universities are facing intensifying pressure from the Trump administration to eliminate diversity programs and remove international students.

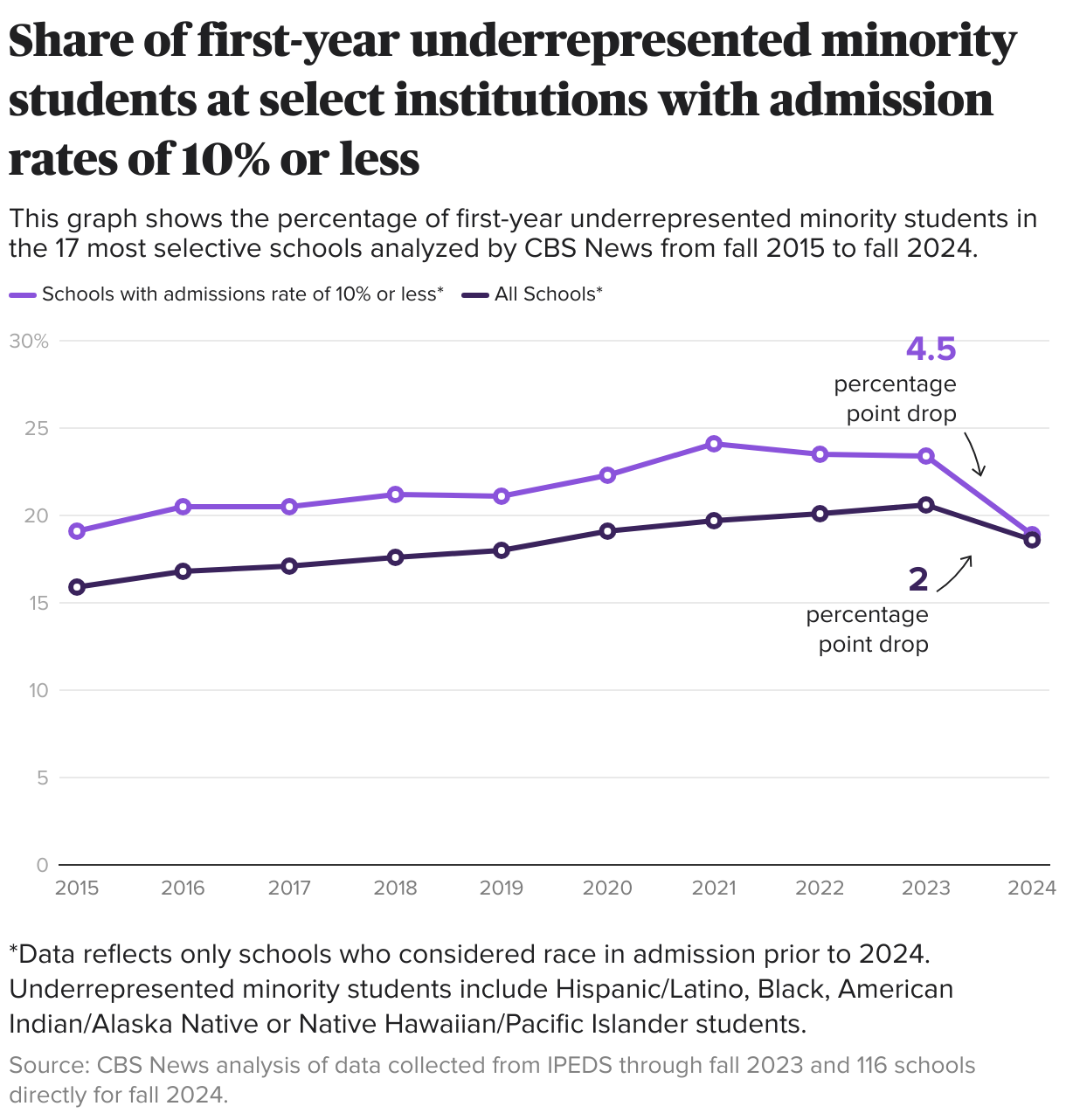

CBS News gathered first-year enrollment data from 116 colleges and universities, 76 of which considered race in admissions before the Supreme Court ruling. The data showed the share of underrepresented minority students among those schools decreased by about 2 percentage points from fall 2023 to fall 2024.

Underrepresented minority students include Hispanic, Black, Indigenous or Pacific Islander students. These are groups that have historically had disproportionately lower rates of college admissions.

Among the 35 schools that did not previously consider race in admissions, the share of underrepresented minority students remained roughly the same, suggesting the ruling may have influenced diversity on campus.

Five schools did not report whether or not they considered race in admissions.

CBS News found the drop in diversity was even sharper at the most elite colleges and universities. At 17 schools that accept less than 10% of applicants, the share of minority students fell nearly 5 percentage points. This includes schools like Dartmouth, Princeton, Cornell, Brown and Tufts.

Despite this, the most selective schools still had a slightly higher share of underrepresented minority students than other institutions we collected data from.

While the one-year drop itself seems small, the fall 2024 semester was the first time the percentage of underrepresented minority students had decreased since at least 2015.

Black students experienced perhaps the most significant one-year shift. At the 76 schools that previously considered race in admission but no longer do, the average share of Black students dropped from 6.4% in fall 2023 to 5.3% in fall 2024, the lowest level in the data collected since at least 2015.

Early data “sends up a warning flag”

Dominique Baker, an associate professor of education and public policy at the University of Delaware, said it’s still too early to draw any concrete conclusions from this data.

“We like to look at trends over a longer period of time, because in any given year, we could see a blip that goes up, a blip that goes down,” Baker said.

But if the trend continues over four years — by the time these students are seniors — it could mean the campuses they attend will be significantly less diverse.

For Baker, this “sends up a warning flag.”

“We’re now starting to see … early indicators that we might be seeing a negative trend developing in the share of students of color who are attending, particularly the underrepresented minority students that you all are talking about attending more selective institutions,” she said.

She pointed to research out of California, one of the nine states that had banned affirmative action prior to the Supreme Court ruling.

A 2020 study found that enrollment among Black and Latino students at UCLA and UC Berkeley, the more selective campuses in the University of California system, fell by 40 percentage points after voters outlawed race conscious admissions (the state ban passed in 1996 and went into effect in 1998). It concluded that California’s ban on affirmative action exacerbated socioeconomic inequities among Black and Brown students.

Desmond Kuhn, an 18-year-old sociology and urban studies major at Columbia University who identifies as African American, said the Supreme Court ruling happened as he was starting to apply for college.

“It’s very discouraging and also makes it harder to reach a lot of these, especially private elite universities, because a lot of generally Black and Hispanic communities don’t have the same resources as, say, White and Asian communities,” Kuhn said.

He said he saw the difference in resources between his predominantly Black high school in the suburbs of Detroit and the predominantly White private boarding school where he retook his SAT.

Columbia University published first-year enrollment numbers for fall 2024, but in a different format than the federal data collection, which we used in our analysis. In Columbia’s reporting, the percentage of students who self-identified as Black or African American dropped from 20% for the class of 2027, to 12% for the class of 2028. (In this reporting method, students can identify with more than one race, whereas in the federal data, students could only pick one.)

Columbia declined to provide CBS News data in the same format used for the analysis of other schools, so the university is not included in our overall findings.

Other factors at play

Across all schools, the share of students who did not report their race in enrollment records (and were classified as “unknown”) grew significantly — the largest spike since at least 2015.

While the data suggests the start of a downward trend in the share of underrepresented minority students at colleges and universities, the jump in the “unknown” category means the racial makeup of the class of 2028 could be different than what is being reported.

If many of the students who did not report their race were White, then the share of White students would be higher than the reported data might suggest, lowering the share of underrepresented minority students. But if the students who did not report their race were Black or Hispanic, then the share of Black or Hispanic students may be higher than what is reported.

“That’s part of the really, really big challenge of … charting and thinking through who is currently enrolling at colleges and universities after the Supreme Court decision,” Baker said.

Tom Delahunt, the vice president for strategic recruitment and enrollment at Southwestern University in Texas, said the drop in underrepresented minority students could also be because of problems with the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, that were at play while the future fall 2024 freshman class would have been making decisions about if and where to go to college.

Typically, students can apply for the FAFSA on Oct. 1 each year. But in 2023, the form wasn’t available until Dec. 30. As a result, schools couldn’t offer financial aid on time because they did not have the FAFSA information, forcing students to wait for delayed offers.

“Delays, glitches, and other issues led to a 9% decline in submitted FAFSA applications among first-time applicants, and an overall decline of about 432,000 applications as of the end of August,” said a report from the Government Accountability Office.

Delahunt said that many of the students who had delayed FAFSAs would likely only make decisions about schools if their families had the money to go ahead without knowing how much they were going to have to pay. But many underrepresented minority students may come from poorer families that could not afford to guess how much college would cost.

Impact of diversity on campus

Experts said studies have found diversity of all kinds, not just racial diversity, is essential to students’ education.

“These studies don’t say that students of color benefit from diverse learning environments. White students also benefit. Every student benefits from a diverse learning environment,” Baker, from the University of Delaware, said.

Jennifer Levine, a first-year student at Stanford University who is half Asian and half Jewish, agreed. She participates in a residential humanities program, where she lives with the same students she takes classes with, a group she described as predominantly White. The uniformity, she said, makes for “a worse learning space.”

“I think that all academic environments are made better with more opinions, more experiences, people who have different sets of knowledge,” she told CBS News. “For me as someone who’s not Black reading Toni Morrison, I can’t offer my perspective on that in the sense of race.”

Stanford’s first-year class has roughly half as many Black students this year compared to last year. Austin Shaw, one of those Black freshmen, said he can see the difference. He lives in a dorm that is themed around the Black diaspora, so many Black students choose to live there.

“All of us are very tight because we’re literally like half of the Black freshman population,” he said of his dormmates. “But when you go out into class, it’s a completely different vibe.”

Shaw said that about half of the students in his high school in Los Angeles were Black. One of the reasons he chose Stanford over other California schools was that it had a higher proportion of Black students.

“You become an expert on the subject of being Black, or you feel like you have to represent, or you feel like you have to talk for your community,” he said. “When I was in high school, where half of the class would be Black, you wouldn’t have that expectation.”

Other ways to ensure a diverse student body

Delahunt, of Southwestern University, said this ruling, along with other restrictions on diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives, have made his job harder. He said his goal is to try to ensure that the student body reflects the community around it in Georgetown, Texas, just north of Austin.

This is so “when they leave … they are ready for the next step of entering into society as a contributing member of society, that they understand how to work together. That we’re going to have differences, and that’s OK. How to work through those differences, how to work together to solve problems,” Delahunt said.

Now, without being able to see race and ethnicity on admissions forms, he must rely heavily on recruiting from high schools where he knows the population of the school is reflective of the mix of students he wants to come to Southwestern.

“Our job hasn’t changed. Maybe the way we do it has to change a little bit. But our goals are the same,” Delahunt said.

Richard Kahlenberg, director of the American Identity Project at the Progressive Policy Institute, said that if schools were to consider socioeconomic status instead of race, they could still increase diversity on campus. Kahlenberg testified on behalf of Students for Fair Admissions in support of the ruling ending affirmative action.

With data obtained through the legal process, he and an economist ran dozens of admissions simulations and found that considering socioeconomic status and ending preferential admissions for legacy students could increase diversity at Harvard and the University of North Carolina while maintaining academic caliber.

“If there were some universities that did not see declines in racial diversity, as we know there were some, then it’s incumbent upon those institutions that saw larger drops to learn what happened,” Kahlenberg said.

He added that universities and colleges have argued that this method would be far more expensive, as it would increase the amount of financial aid the schools have to provide.

“It’s not that race-neutral alternatives are ineffective, it’s that they cost more money,” he said.

Some schools have increased socioeconomic diversity. UNC increased the number of students with federal Pell Grants to nearly a quarter of the class. Both Yale and Dartmouth’s first-year classes had the highest-ever share of first-generation and low-income students, all while increasing their share of underrepresented minority students.

All diversity, equity and inclusion efforts are at risk

As universities adapt admissions processes to maintain diversity, they risk butting heads with an administration that is seeking to end all diversity, equity and inclusion efforts.

The Department of Justice announced at the end of March that it is investigating four California universities to assess their compliance with the Supreme Court’s ruling.

University of California schools, which have not been allowed to use race as a factor in admissions directly since voters passed Proposition 209 in 1996, recently moved from using test scores and GPA for admissions to a “comprehensive review” process.

That process looks “at multiple factors beyond courses and grades to evaluate applicants’ academic achievements in light of the opportunities available to them and the capacity each student demonstrates to contribute to the intellectual life of the campus,” according to the University of California’s admissions website.

UC admissions for underrepresented minority students has increased since the initial drop following Prop 209, with the nine universities admitting the largest share of underrepresented minority students in its history in 2021. But the schools’ student bodies are still less diverse than the California population or the cohort of high school graduates who meet UC admissions requirements.

Underrepresented minorities make up about 32% of the UC fall 2024 freshman class. But they make up 46% of Californians and more than half of the state’s high school graduates who meet the minimum academic requirements to get into UC schools.

However schools choose to adapt, ignoring race in wholistic admissions entirely is unrealistic, said Levine, the mixed-race Stanford freshman.

“Parts of your identity can’t be separated from your field of study, from your interests, from what you do,” she said. “My identity is tied to the kinds of things I’m interested in, what I wrote my essays about to get into college. Taking out my race from that is not going to take away the fact that that is part of who I am.”